An online gallery for concerned documentary photographers, curated by the CBDP.

This page is devoted to exhibitions of documentary photography, it gives the photographers at the CBDP a platform to show their projects to the public.

We share their documentary practice through visual examples.

The CBDP is committed to providing this online exhibition space for our documentary photographers. This way the work can be shown to as wide an audience as possible.

Support from the photography community is great but our aim is to place the work in the main stream so that non photographers can also learn about the world and its stories. Please scroll though the various photo exhibitions, all are dedicated to social documentary photography.

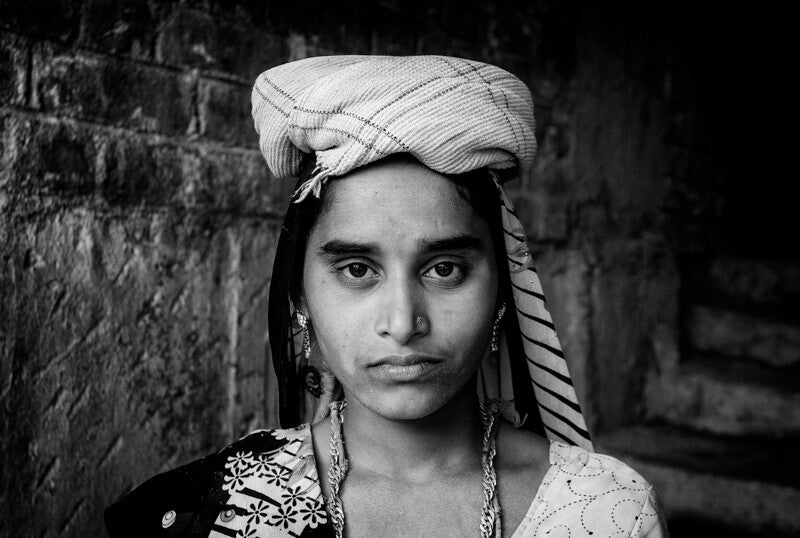

Fuad Sarkar is an Indian documentary photographer and he has shared with us, his images from a project he made, alongside the Santal's of India. The Santals represent one of the oldest indigenous groups in Bangladesh. The tribes concentrated in the districts of Rajshahi, Naogaon, Nawabganj, Dinajpur and Rangpur. Their habitat is close to forests, jungles and areas accessible to nature, in following a symbiotic relationship.

Images by documentary photographer, Fuad Sarkar.

It isn't very often we get to see documentary photography from the State of Iran, the region being for the most part either closed off to westerners or difficult to travel in. Thankfully the CBDP has a contact out there and so we are able to share with you a handful of images made recently of children who's lives and potential futures couldn't be more different than our own.

We hope to add to this body of work over the coming months and years...

Documentary photographer Masoud Naji shares his work from Iran.

Children of Iran.

Documentary photos & text by

Masoud Amin Naji.

Copyright 2024.

"This is the Middle East. It is made up of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran. The people here are kind-hearted and knowledgeable people, but due to various reasons, such as tribal wars, poor economy, cultural and religious differences, they are forced to either give up their children or use them to make ends meet. They force children who are deprived of education, affection, happiness, joy and play, even though they don't like it. The children are forced to work and lose a good life full of happiness, health and respect without wanting to. Maybe something can be done for them to return to the normal cycle of life. There is no doubt that they are brilliant talents.

There is no place for women and girls in prison.

There is no place for mothers in prison. There is no place for children on the street.

A child is not even a criminal in prison.

You may have heard these sentences in the headlines of newspapers or in movies like Bicycle Thief or Ladri di Bicycle, but here with these documentary photos we want to talk about the mothers who have to keep their children in prison with them due to various crimes.

After all, for what crime and mistake should the whole life and happiness of a child be ruined, this is the Middle East and such things happen a lot, let's be together for once and work for women and children so that they can have a normal life".

Masoud Amin Naji.

As we arrive in 2023, we start the year with this interesting set of images from documentary photographer, Nicolas Ghirlando. This is a slight diversion from our usual style, in that the work is a highly personal approach to examining the experience of his own journeys made by rail. He captures well the sights and atmosphere of rail travel and you can almost feel the clickity-clack of wheels on tracks and the passing of time. He explains also a unique approach to the use of instant pictures, it seems his life is a constant documentary. So sit back and enjoy, the view from the train.

The View from the Train.

Documentary photographs by Nicolas Ghirlando.

London. Copyright 2021-22.

Over a period of eight months I photographed the journey from the window of the train. These journeys were the same train line from Norwood Junction in South East London to London Bridge station and taken at various times of the day. There was no particular pattern to the journey times, nor was there a strict brief to at what point or location I would take the photo.

They became almost automatic images and a record of time and movement. Journeys and the passing of time has always been a focus for me when making work, for example photographically documenting on Polaroid the journey from home to an exhibition of my work, which was actually the document of the journey from home to the show -- the actual work only appearing on the wall when I arrived at the opening.

Other times I have photographed a drive from London to Bournemouth in a more regimented way, taking a photograph every fifteen minutes. These collections, to me, capture a period of time and distance, preserving it as if trapped in amber. They become image fossils, the light frozen on film. This series, 'The view from the train' while made over a specific period of time (although not specifically intentional) can be seen as open ended and can be added to as long as I travel on trains with my camera. What you see here is neither the beginning or the end, but a slice. There are images from the same train tracks taken many years ago in my archive and there will be many more in the future. But for now, this is a document of eight months in 2021to '22.

Nico Ghirlando, London January 2023

The fifth exhibition of documentary photography in our series and bringing 2022 to a close is this work by James Moverley. He has followed several of us locals into one of the last "Free Mines" in the Forest of Dean and produced a set of classic images which we are sure you will enjoy. James is an active miner himself and spends many hours "under the Forest". Recently James produced a book of this work to a highly responsive reception.

Under the Forest.

Documentary Images by James Moverley.

Copyright 2022.

Freemining is unique to the Forest of Dean. The Iron ore and coal fields have been mined for over a thousand years in the area this became known as free mining. Freemining became regulated in 1682 and the Freeminers mine law court was formed, sitting at Speech House in the heart of the Forest.

In 1831 a Royal Commission was set up to inquire the nature of mineral interests and free mining customs in the Forest of Dean, this brought the 1838 Dean Forest Mines Act, which forms the basis of free mining laws.To be eligible to become a freeminer the law states the requirements as:

"All male persons born or hereafter to be born and abiding within the said Hundred of St Briavels, of the age of twenty one years and upwards, who shall have worked a year and a day in a coal or iron mine within the said Hundred of St Briavels, shall be deemed and taken to be Free Miners."

The Dean Forest (Mines) Act 1838

Modern day free mining has changed very little from the boom during the industrial revolution, be it the mines are worked on a much smaller scale, with just a handful of free mines still operating. In many of these coal is still dug by hand using Picks and shovels, Timbers also cut and erected in the traditional manor. However other aspects of the 1838 act problems have arisen. It is now uncommon for potential freeminers to be born in the Hundred of St Briavels as the majority of births occur in Gloucester Royal Hospital. This leaves the eligibility almost non existent.Currently there are miners working in free mines with the aim to keep traditions alive, they may not be eligible to become freeminers themselves, but by still operate at the same high standards and traditions, these miners will have the skills to keep Freemining alive and pass on their skills to the future freeminers to prevent this ancient tradition from ending.

Wallsend Colliery is just one of such free mines in the Forest of Dean, with a workforce of 11 people, the coal is still worked and skills still passed on. A very friendly bunch, always willing to stop and chat to passing public about what they are up to, they are always met by amazement that they continue to mine coal.

Over the years several photographers have documented Wallsend Colliery, I considered when doing this project how I could add to their story, how I could portray the underground world of the Forest of Dean. Well, I am one of those miners who dig coal by hand, this has given me the chance to photograph the miners as they work during the highs and lows in keeping traditions alive.

All the photographs have been taken over a two year period whilst I have been working with the unique characters Under the Forest.

James Moverley.

2022.

Please click the arrow to see the documentary photographs.

Our fourth exhibition of documentary photography is English Photographs by David Cross, Founder of the CBDP. This colour work was made as an immediate response to what England looks like in the aftermath of Brexit and Covid. The inspiration is American in style and attitude and is a new approach by the photographer.

English Photographs.

Documentary Images by David Cross.

Copyright 2022.

It struck me that I had grown up feeling a connection to Europe and its ideals. Le Tour de France was the beginning, the mystique of the towns, language, mountain ranges and the art. All delivered in an 1 hour long tv show via Chanel 4. My interest in the Secondary School education peaked with European Studies which included a rich history and was presented by a teacher who was clearly in admiration of Europe. Three years later I also discovered the photography from Europe and that changed my life on the spot, suddenly surf photography didn’t seem quite so vital. I have always believed that together we are stronger, more progressive, more lenient and well, more interesting!

By the time that the Brexit debacle some 35 years later had arrived on our doorsteps and red buses it struck me that being in the E.U was also protecting us from our own government. With the E.U. we were locked in to something that looked like a positive vehicle, okay it had its problems but everyone was being accounted for and fair play all round felt like the end goal. Out of the E.U we would be at the mercy of our own government and the pockets they appear to enjoy filling. We are endlessly fobbed off that Covid is to blame, yes it has played a role but I believe that the end result of the Brexit Trade Deal is a major factor and for those who reside mostly on the bitter end of capitalism things are certainly not panning out. The latest “plan” is to cut Taxes for the rich and hope the poor believe in the trickle down effect. Thankfully this was terminated with a classic “U” turn, a dismissal and blame passing, all very British. It’s worth noting that when the Brexit deal was done and the contents published in a book, it wasn’t openly scrutinised or discussed by the media. I have never heard mention of it which is peculiar considering the country waited two years the for details of the final outcome.

The work in this series of documentary photographs looks at England post Brexit and Covid. I have tried to examine what is left of the country that was wanted so much by some of the inhabitants. The photographs study random parts of the country and present at their heart, England. This is what is looks and feels like to be here. Away from the dessert areas inhabited by the upper-middle classes things are different, the hope came and left town without hanging around. The people either work hard or sit on the breadline and the difference isn’t as broad as you would think. Money from central funding organisations isn’t getting through or doesn’t exist. Crime, drug and alcohol use is standard and you can sense this in many parts of the UK, you don’t have to see it, the signifiers abound. Of course people work hard, keep their houses nice and polish the beloved car at the weekends but they share space with those in poverty. It makes for an interesting community spirit and you don’t have to scratch too far below the surface to hear a sad tale.

We move towards ever more uncertain times. Climate crisis is right here and happening. The cost of living crisis is also here and feels real to everyone, well, almost everyone.

We might live long enough to experience a nuclear exchange on the very edge of Europe and I’m not alone in feeling that outside of the E.U. we face a large and uncertain burden.

Can government rebuild trust and unify the nation of all creeds and colours to face these challenges. Can we the people see a way forward? Are we capable of real change that will like it or not, come with a deep cultural shift.

David Cross

2022.

Please click on the arrow to view the images.

For our third online documentary photography exhibition, it gives us tremendous pleasure to show the work of Sofia Conti. Her documentary photographs are a perfect example of the genre, she is original and brave, working on important social stories from the margins of what some would call, "normal life". Sofia is happy to work on these fringes and bring us a close and honest account, she also shares the work locally, ensuring that her subjects are very much a part of the future of the photographs.

Return, O Backsliding Children.

Documentary Photographs by Sofia Conti.

Copyright 2022.

‘Return, O Backsliding Children’, is a multi-media based collaborative project that explores each participants connection to crime and how it has indirectly and or directly affected their way of life. Around eight years ago I settled in the East End of Glasgow with my fiancé who was brought up in the area. As a non-native I noticed significant differences in the environment such as a lack of housing, anti-social behaviour issues, limited career prospects, poor health, addiction, and high levels of depravity. From the continued research conducted over the last two years, I discovered that Greater Glasgow had the second highest crime rate of 682 per 10,000 population between 2020-2021 (Scottish Government 2021). It was at this pivotal moment I believed further investigation was required on the subject of crime and other issues closely connected to it, as my collaborative conversation sessions indicated that crime had entered many of their lives in a variety of forms.

Throughout the process of the course, I have built strong relationships with a wider network formed by a combination of fellow residents, charitable organisations and local community groups willing to participate. The trust has only been established by my complete transparency, privacy and communication skills that allowed the collaborators to openly discuss their stories of crime in strict confidence on a much deeper level. The sensitive nature of crime has been heavily considered as the ethical representation of the collaborators and the Greater Glasgow community was paramount as they are the primary audience. The project’s intent is to spark conversations on themes such as people, place, crime, trauma, ethics/representation, poverty, social class, identity, and memory which all play a part in how the Greater Glasgow community is perceived. As a gay female, non-native, current resident of Glasgow and a victim of crime myself I believe assisted with portraying a more empathetic response to the issues raised.

‘Return, O Backsliding Children’ is directed by the personal experiences of the collaborators along with my own subjective view as a photographer who resides within that very community. Incorporating a varied range of multimedia formats (photography, moving portrait, text, audio, and an interactive artefact) within the project was important to show that “In teaching us a new visual code, photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe. They are a grammar and, even more importantly, an ethics of seeing.” (Sontag 2008:8). Hosting a free community exhibition acts as a safe environment for the collaborators to vocalise their experiences, the community to see themselves and for outside viewers e.g., local politicians to stand up and pay attention (secondary audience). This will ultimately encourage the audience to consider the strong body of work to spark conversations on what changes are required, to alter the stigmatized view imposed on the good people of Greater Glasgow and beyond who have been touched by crime.

Artist Biography.

Sofia Conti is a Glasgow based award winning social-documentary photographer, who began her photographic journey as a mature student in 2017. Currently Sofia is finalising her studies at Falmouth University (Falmouth Flexible) where she aims to achieve a MA Photography degree that will enhance her practice. Collaboration for Sofia is an extremely important part of the work produced especially when exploring social inequalities within various communities including her own. Her collaborative process is about depicting the people and the connections to their environment. Sofia’s intention is to ethically represent communities that have a distorted view imposed upon them. By empowering each collaborator to tell their story, the hope is to enlighten the audience on the issues raised to change preconceived notions.

Please click on the arrow to view the images.

Welcome to our second documentary photography online exhibition. This time the work featured is by photographer Adam Lloyd Monaghan. Based in Finland the documentary images look at a feature we are all aware of, the redevelopment of our urban spaces.

Suvilahti Redevelopment. Finland.

Documentary Photographs by Adam Lloyd - Monaghan.

Copyright 2022.

...I have struggled to write an opening paragraph. Each draft ends up shooting down artists, the art world, artists explanatory texts and our self-congratulatory ‘Look at what I’ve done’ environment. Therefore, ultimately, each version took solid aim at myself and the last thirty years of picking up cameras. But maybe that is a fair reflection, since I really don’t take it all that seriously.

At its most basic, I want to record how Suvilahti looks at this stage in time and how the space is used, with festivals, businesses, skaters and graffiti painters… to name but a few of those who currently inhabit the area.

I accept that perhaps these photos don’t appear that special or even interesting at this juncture. But I know, from my involvement in photography over the years – and that includes many situations I didn’t photograph and wish I had done - that once these things have gone, the remaining photos do start to gain a little more flavour. When I see a photograph of 1980s England, I hone in on things like a Mark II Transit van. At the time, it was so every day as to be totally irrelevant. But looking back, it is those little details that immediately contextualise the image, historically, geographically, and culturally. I really like that aspect of photography.

I guess there is an element of flattering the audience. It is tipping your hat to those that remember, by making an ‘I was there’ kind of memorial. Culture does this all the time with photographs of Woodstock or The Cavern Club. At its ‘worse’ that is about division and creating an in-crowd of initiates. But at its best it is about sharing, building empathy, re-connecting and remembrance. And I think that is true even for something as unspectacular as a rubbish strewn piece of waste land with a skate park. Because I do consider these spaces are important in our collective psyche about youth or leisure or formative experiences.

Additionally, perhaps there is also a sprinkling of midlife crisis. One can see the speed at which one’s own life is flashing by and one tries to grab at something to stop it disappearing. Added to that is the nagging part of your brain going: is this the start of my older self’s reluctance to change? And then layered on top of that is the pace at which gentrification and turnover of information makes something disappear from our general collective memory. So one is simultaneously aware of both one’s own life rushing past and then witnessing the environment doing the same. I think good photography can utilise all of that to make itself speak more powerfully.

I do feel a little fraudulent, in as much as I am not a skater. I am not a graffiti artist. I am an outsider in that space. I guess, as I’ve said previously, maybe it is as an immigrant and having witnessed similar changes elsewhere, coupled with just how unbelievably rapidly it’s happening in Helsinki, that I find a legitimate ‘in’ into the situation at Suvilahti. That is how I feel justified in having a voice there.

And finally, of course, Suvilahti is visually a very interesting and dynamic place. And that ultimately has to be the most important element, otherwise one would just write about it. Why make visual imagery if it is not visually interesting? I do want to take photos that have that historical value but they still have to be strong images. I don’t know if I always succeed in that, but that’s fine too. I’m not saying my view of the world or my photos are perfect. They’re just stuff, added to a world of other stuff taken from a specific perspective at a certain point in time …

OK, I take it a little seriously. But only sometimes.

Suvilahti is an area of Helsinki that has been home to a variety of energy plants, from steam turbines at the start of the 20th century and then gas production and storage, through to the still operational Helsinki Energia power plant. Many of the structures have been classed to be of National significance. Since the decommissioning of the gas works, the site has been used for many cultural events, such as the Flow Festival (since 2007) and Tuska Festival (since 2011). There is a skate park and in recent years a long ‘official’ graffiti wall. The area is undergoing rapid changes. Lesser buildings have been demolished. The graffiti wall was removed in June 2022 and the skate park will probably not survive through 2023. The aim is that Suvilahti will become a cultural hub. Proposals have been made for the area to house HAM (Helsinki Art Museum) and many other small businesses and cultural centres are opening in the protected buildings.

Please click the arrow to progress.

Our first exhibition of documentary photography was an exclusive and we were very honoured to be able to show this important work from India, by photographer Bharat Patel. Looking closely at the female condition these haunting images will remain in your memories for many years.

Women in the Construction Industry - India

Documentary Photographs Bharat Patel.

Copyright 2022.

Over the past several decades India has seen a boom in the construction industry. According to prevailing practice in the construction industry, the owner employs contractors who undertake the task of supplying labour and material and supervising the building. Many contractors and agent have set up shop to supply the labour force needed for such rapid development.

Of the female work force in India more than 90% are in the informal sector. They do not have regular salaried employment with welfare benefits like workers in the organised sector. They are usually illiterate who make a living through their own labour.

In a typical work format at construction sites, the men work as masons while the women work as unskilled labour. Women’s task is of preparing cement and transporting bricks to where they are needed. This arrangement seems to be well suited for a husband-and-wife team or as a family unit. Over many visits to construction sites, in small villages and cities I was fascinated by the amount of work the women were undertaking. Many had their young children at the site, who needed constant attention while they carried out strenuous work. Some working while being pregnant and some working only a few days after having given birth. Most women were between 25 to 45 years of age but many as young as 15.

These images taken over several years show women in the construction industry using their only asset – their labour, carrying out back breaking work under hazardous conditions in an unprotected work environment.

Bharat Patel.

27/07/2022

Please click on the arrow to progress.