Surfboard Shaping & the Rise of Machines.

Papa he’e nalu: Towards a continued Counterculture.

North Devon, England.

Photography & text by David Cross.

The door is pushed open and the row of fluorescent lights on either side of the room respond to the click of the switch on the wall. They buzz and then flicker and pop into life to reveal the synonymous set up, found all over the world. A space that looks sparse but is home to the symbiosis of hydrodynamics, art, and craftsmanship. Honed over decades these elements come together at the hands of a Master Shaper to create the perfect wave riding vehicle. But like the seasons that come and go and bring change on the wind, so too a change has arrived in the culture of surfboard shaping and manufacture.

Surfing is caught up in many traditional values, and with films, characters, and monikers such as, endless summer and the search for the perfect wave, the scene is easily set. The varied renegades, crazies, an endless list of inventors, designers and free-spirited world travelling vagabonds, as well as big wave pioneers and beach life spiritualists have shaped the core of surfing since its arrival in the U.S. from the Hawaiian Islands around 1900/1910.

Surfing’s cultural codes and rhythms are rooted in a period just before mass consumerism and globalisation. Genuine and original characters, all said to be “freestyling” in an experimental life, experienced and projected to everyone else, what was possible. Sex, drugs, and beatniks may have been an attraction on the sandy beaches, but for others, there were waves to be found and tamed, this would take time and serious commitment. It would also require exacting surfboard shapes and designs.

The very earliest surfboards were produced from trees by the Polynesians and date back to 1200 A.D. These “logs” were crude and weighed anywhere from 35 to 60 kgs. and looked much like an eight-person rowing boat, but without the seats. The finest native trees were apparently saved for Royalty. Finless, these undoubtedly dangerous boards were ridden straight to the beach, which crucially meant that several people could share a wave. Things couldn’t be more different today, where sharing a wave is construed as “dropping in”, used in a derogatory sense and will likely yield some verbal abuse, or worse in some areas.

When surfing was introduced to the U.S.A. it didn’t take long for the development in the technology and design to begin. George Freeth in the U.S. cut his board in half and started a minor revolution, in 1926 Tom Blake “invents” the first hollow wooden board, a version of which, refined by U.S. based Grain Surfboards is still popular today. Likewise in Hawaii, as early as the mid 1930’s the development had already started on the proportions and rail shape – the outer edge of the surfboard - and heralded what was called in surf parlance, the Hot Curl style of riding. This change in length, width and weight over the years is dramatic and propels surfing movement but the surfers have to wait until the introduction of 3 fins, balsa and later in 1952, Polyurethane closed cell foam, before they can push the boards and themselves to the limits of performance and survival.

PU foam cores, called “blanks” are the game changer, boards are now much thinner and narrower than before. The new designs didn’t appear overnight, it took endless tweaking and experimenting and inspirational lightbulb moments of genius. It also required waves of consistent and mechanical perfection, these were found but the tides and swell do not always align, and so there are tales of experimental boards shaped and “glassed” overnight so as to ride the same swell the next day before it ebbs away. Eventually the modern surfboard was born and now surfers could ride anywhere on the face of the wave, even deep inside the “tube”.

When big wave pioneer Laird Hamilton said when talking about large waves in the film, Riding Giants, “… it’s defined decision making. You don’t kind of take the drop into a 100-foot wave – you either do it or you don’t” - he wasn’t just speaking for himself and friends in the Strapped Club, he spoke metaphorically for a global counterculture and size doesn’t really matter.

By the 1990’s, the deeply embedded ethos of big wave riding and with it, high-tech boards had progressed to a place on the Island of Maui, called Jaws! Here, in front of a large cliff under a pineapple field, Hamilton, and others used jet skis to initially tow them into the waves. Which are quite simply majestic natural wonders of the earth, that leap out of the ocean at a size and speed that is quite incomprehensible.

Throughout the history of modern surfing the surfboard shaper has played arguably the most crucial role, many have been and are today, some of the world’s best surfers. In the natural order of things, it is no surprise that some of the first “tow-boards” as used by the Strapped Club, were shaped by Hamilton’s father (by adoption), Billy Hamilton, himself something of a legend in the area of shaping.

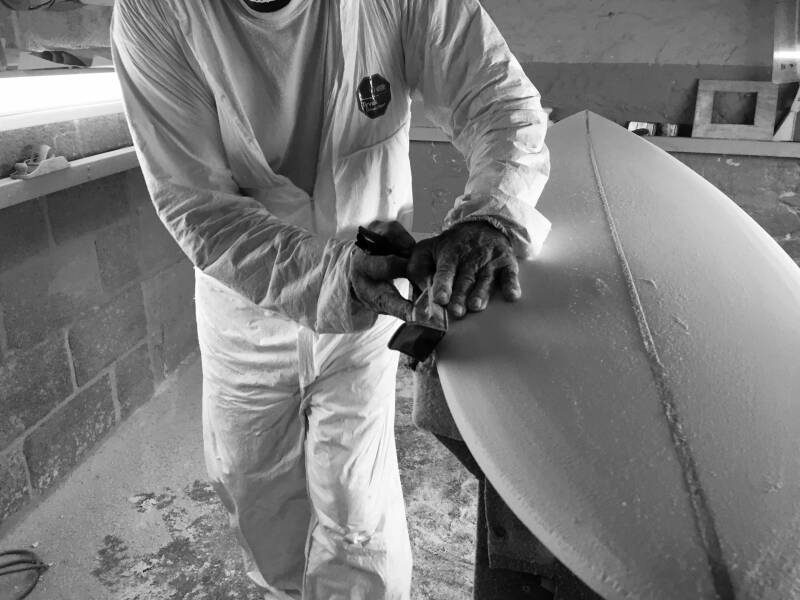

Photo at top:

The hands of a Master Shaper - Paul Blacker.

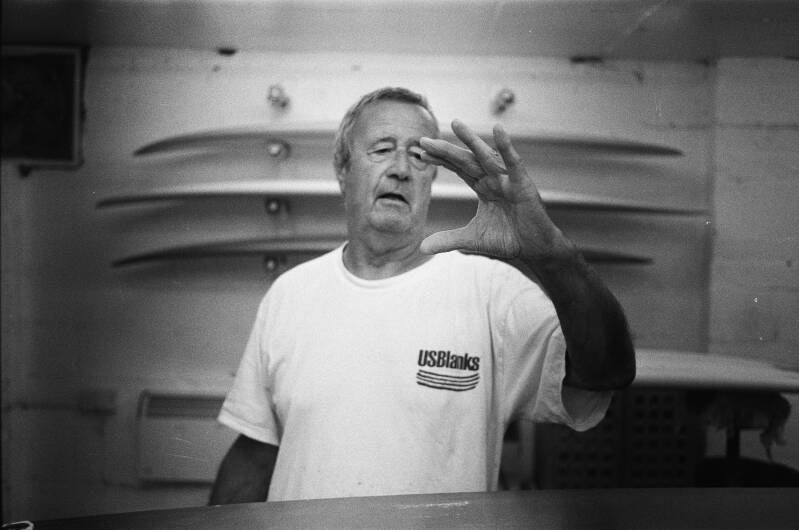

Photo above:

Paul discusses various outline templates which are crucial to the individual ‘board. A combination of elements come together to make the perfect shape.

Photo above left:

A surfboard blank and “Clark” adjusted electric plane. These planes are a rarity today and it can be said that the closure of Clark in the U.S. heralded or opened the door not just to other brands of foam but also the widespread acceptance of alternative materials. One of the leading brands today is US Blanks.

Shaping surfboards is complicated stuff, areas of the 'boards surface are referred to as, “the wetted area” also the “rail” shapes, “foil” and “rocker entry point” must be millimetre perfect on waves of consequence and all boards made by the Masters. Although most shapers agree on certain principles, many have their own unique take on the design aspects that wouldn’t be noticed by the uninitiated, there are some that have an acute understanding of hydrodynamics as they relate to surfboards. In large waves it is crucial that the edges and contours are correct, as Darrick Doerner famously said, “You can die. Real quick”. And all too sadly they do. Recently Veteran Brazilian surfer Marcio Freire passed while riding a giant wave at Nazare, Portugal. This is a famous spot that yearly attracts the best riders in the over fifty club.

That’s wave height in feet, not age in years.

Photo left:

Using the electric planer to "thickness" the foam blank.

Here in the UK the hibiscus world of surfing as was regularly portrayed in British magazine, The Surfers Journal is replaced with cold grey days, onshore winds, and a general lack of regular quality waves. But that hasn’t stopped the surfing movement from taking hold and establishing itself into a culture and business enterprise with a value in the region of £1.8 Bn per year. And also, according to the data at fact.MR, an estimated 500,000 Brits, and I’m occasionally one of them, don their wetsuits and dive into the mostly frigid Atlantic all year round. The growth is expected to be in the region of 6.3% over the next ten years across the UK and Europe. The data from the surf industry, in this case, House of Surf, state that there were between 13 and 24 million surfboards sold annually across the globe in 2022. For those who noted the switch to polyurethane foam, and know a little about the chemistry, that’s an awful lot of Toluene di-isocyanate, a by-product of the petrol-chemical industry. It would also involve several thousand barrels of polyester, also from the same industry. Did someone say, hibiscus? The move from timber to plastic was a move of consequence, now that we know about the environmental impact, not just of the fossil fuel industry per se but also that of the surfboard industry, like it or not, the industry is centred around toxic and hazardous materials. It is in this area that perhaps the original small-time shaper, making one board at a time, can find a niche, and keep the tradition of handmade custom shapes alive. But there is a resistance to new materials, as this affects the feel of the board.

Photo left:

After the planer, the "surform" tool is used to further refine the bevels on the deck and rail.

The change mentioned at the beginning of this piece is that of board production method and location. The history of the modern surfboard was built by hand in shaping shacks and sheds, you had to know what you were doing if you planned on selling them. Precision and symmetry are key points, for many it’s an Art, for some a process of simple reduction using carefully cut bevels. Very few really understand the hydrodynamics, but everyone learns by looking, riding, basic copying and having feedback from team members. New ideas are then transferred, understood, and adapted for the local wave shape, size, and power. It can take years to truly get a grip of the skills involved. It really is a fusion of hand craft, high theory or guess work.

For many the emphasis has now changed, and the majority of surfboards are made abroad - there are factories in China and Thailand. They produce what many believe to be a fantastic product and the pricing is cheap. Cheaper unfortunately than the domestic models and this is having an impact that some say is harming the traditional skills, brands, and infrastructures. For the most part the designs are proven shapes and with digital technology and C.N.C machines the latest tweaks and trends can be sent to the factories at the touch of a button from the comfort of your beachfront real estate. Surfing is about to become a victim of its own globetrotting, free as a bird approach to life. The talented and tech minded designers, we won’t call them shapers, have embraced what is now possible, applied the principles of global commerce and cashed in.

For many traditionalists this could spell a level of disaster as currently there are no taxes applied to surfboard imports from Asia into the U.S.A. Here in the UK the situation isn’t so acute but regardless, almost every surf shop in Cornwall and Devon (U.K.) has boards for sale that are machine made in Asian factories, and even here at home. This does on a positive note play into the hands of the talented shapers whose products are superior and made custom for the client, but their numbers are dwindling, and they rely on enough customers willing to pay out as much as £200 and even £500 extra, and wait for the product. It also relies on the successful and timely import of quality foam blanks from abroad. The best comes from the U.S.A. and there have been hold ups throughout 2022 and 2023.

But a walk across the majority of Britain’s surfing beaches implies a dwindling customer base, virtually all are C.N.C. The choice is cost or tradition and of course the problem is, the young of today know a new tradition and it’s digitally based, the kid of today has no interest in the stars of the last few decades. A twenty something lifeguard I met, had no idea there was a shaper just up the road from his local break - about to retire.

Photo above left:

One of the hardest skills to master, the final rail shaping.

Photo above right:

The Master, Paul "Blackie" Blacker, with one of his Lightening Bolt 'boards.

Photo left:

After so many years and thousands of boards made, Paul has an impressive muscle memory and is able to test any board for a “well shaped rail”. His approach is a world away from the C.N.C. shaping machines which were first seen during the mid 1980’s.

For some the writing was on the wall, the end of an era, for others such as American Rusty Preisendorfer, the technology enabled not just the growth of his brand but also faster production and millimetre perfect reproductions. It’s an interesting set of opposites, for Paul Blacker every board was a unique piece, evolution in both design and rider meant that few if any boards were actually “repeated”.

Back in the 1980’s as a kid myself, I thought the surf shop was the best place to be if the waves were flat. These establishments oozed mystique, charm, and a sense of wonder. Like the shaping shacks around North Devon and Cornwall, the walls were blessed with photos from the past. Grainy images of perfect waves, sometimes empty sometimes not, “Where’s that”? you would ask, “A secret Spot”, was the reply. How simply perfect I thought. For some of us, surfing offered the ultimate boys adventure, basic escapism, and a route out of the city. Living off the visions presented on the pages of certain magazines, it was all experienced in glorious if imagined, perfectly exposed “Kodak Chrome” - the one time film of choice and a registered trade mark.

One surfboard shaper who has lived the experience with 54 years of foam shaping, is Paul Blacker. For many Devon locals and travelling surfers alike, he is considered a Master Shaper. All of his boards, totalling 5184 at time of writing, were made by hand over a 54-year period and each one a unique masterpiece. He layers the fibreglass, fine sands, paints and adds the fins too. What you buy isn’t just the surfboard product per se, you inherit years of experience and 1000’s of waves ridden, all around the world. He is an encyclopaedia of wave shapes, best size, and wind direction to locations all over the globe. His boards have been ridden by the British and English National Champions and have found their way to Indonesia and beyond.

The Japanese have a phrase regarding beautiful and purposeful things; objects that are born, not made, and “Blacker” custom surfboards easily sit within this system.

During September of 2023 I was able to catch up with Paul as he finished his last three boards before he switches off the lights and shuts the door on the shaping room for the final time. At age 69, and with an aching body and an eye on the clock he has decided that it’s time to stop. I meet a jovial man and am at once transported back in time, for there by the door is a new board, recently made for one of the local legends of the late 1980’s, Neil Clifton. The board is a modern twist on a style used at the time and mostly developed here in the UK by Paul - a quad fin with channels. Paul was a very early experimenter in this design having seen it at its conception while working in a board factory in Australia. He is also the only shaper in the UK and Europe to be a part of the Lightning Bolt franchise – this was an early brand of boards created by surfing’s mega star, Jerry Lopez and partner in 1976 – Paul’s skills were duly recognised by Lopez and as one famous commentator noted, “Blacker is the most underrated shaper” and he’s okay with that, he knows his place in the order of things, he brags a little but in a charming way - you know it’s all true and he genuinely cares less for any ranking position.

Photo left:

A pile of old surf magazines is a good sign. Here Paul and I discuss the merits are various world class waves.

He started at age 15 and knew that he was a shaper. “It felt right and I loved it”, he told me and went on to explain that he was offered an apprenticeship with Aston Martin, but told the guy, in front of the lecture room, “No thanks, I’m going to make surfboards”. I ask if there is a particular board or rider that has stood out for him, he points at a framed photo on the wall and answers both questions with a nod of his head. I sense a softness in him. The photo is of the deceased Nigel Veitch former British Surfing Champion and arguably Britain’s first legitimate Pro surfer on the Tour, with a channelled quad, complete with the Lazer/Blacker logo of the era.

We talked about Veitch’s death by suicide and Paul clearly harbours a streak of pain at his friends passing, as he told me, “I was just about to pick up the phone and call him, but it rang first, I answered… and it was Nigel’s brother, telling me the terrible news”. They say that every board you shape is in some way, physically (or metaphysically) carried over to the next and I wonder if this is the lifeforce that you can feel in some handmade boards. You can’t help but be affected by the loss of friends and perhaps the thoughts and memories that pass through your mind while creating these surfboards are infused, in spirit into the objects themselves. I didn’t ask him this but suspect that he might agree.

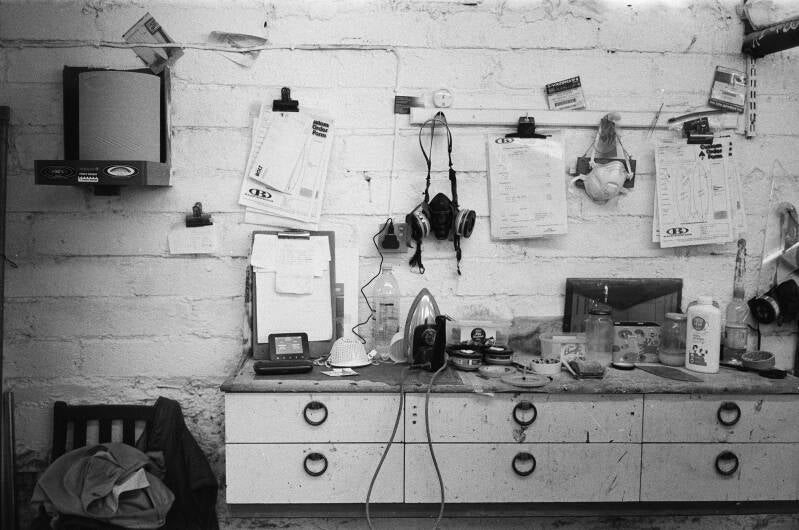

Photo left:

Order sheets for the last 3 boards.

We changed subject and I mention the C.N.C. shaping machines, he raises his eyebrow and gives me a steely stare through his glasses, “It’s not the same thing. Those boards have no SOUL”! He goes on to tell me how he was the victim of these machines and the psyche of some, a few, who have been involved with them. In short, his boards were copied and “bashed out” on a shaping machine, it wasn’t in the ocean-going spirit of things, no magic, just tragic. He’s not alone in feeling that the C.N.C. boards lack that special sparkle, many have commented, others say it’s imagined, in time few will know it even existed. For the few remaining shapers like Paul Blacker, the design and shaping process is a true labour of love. His fingertips have run over every section of the foam, he knows the board intimately, he has already ridden it a thousand times in his mind, at all his favourite places, he understands how it will paddle, bottom turn and race through the barrel. “Surfboards aren’t mass produced, they are more than a unit cost and a shipping number, they are one offs, made for one rider and sometimes one particular wave”, and as Blacker also pointed out, “a machine (and the processes involved) can’t do that and anyway, they don’t feel alive”.

Photo left:

Paul Blacker with the last board made for Neil Clifton - a channelled quad of course.

Having started out so young, in 1969 you can understand the sentiment, although he is in no way bitter, “each to their own, Bro” but the sense of loss, not just tradition but of hand skills and culture is of course on his mind. There are fewer and fewer shaping sheds to hang out at now, the loud screech of the C.N.C and high cost of ownership has changed the dynamic. The staff now stare at a screen sheltered by acrylic glass. Surf shops are like high end clothing boutiques, some don’t even sell surfboards. The game has changed, and the faces are changing too, the winds of time have marched on and there’s no going back.

As Paul will regularly advise you, “Jah will provide” and indeed, Jah has provided a steady stream of customers and furnished him with enough talent and originality to stay in the game for this long and perhaps most importantly, he has revolutionised the lives of those who have passed by his shack to collect a new board. And I for one wish it could continue. Watching him carve a board using just three tools and three bits of sandpaper was an artistic process I will never forget. The approach was precise and deliberate, there was no measuring, no corrections - here was a man in his place doing that thing he was put here to do. His haecceity is Shaper of Surfboards – it’s his very essence as an individual.

Paul is a large man and yet he almost hovered while he worked, long purposeful gliding motions of man, tool, and surfboard foam, all at one and at peace with the world. I have never wanted to own anything as much as I wanted to own that surfboard, it was perfect, and it felt like a shared experience. Personally, I don’t see how you can truly replicate this relationship of shaper, surfboard, and rider, as it is symbiotic, axiomatic, locked in.

The effort, although masked by talent is certainly there and it’s clearly very unique to you. Something I had felt since age 14 suddenly banged hard in my chest – this surf culture runs deep. Blacker’s professional presence will be missed in the shaping bay and as you would expect, the locals, who having heard that the Master was about to hang up his tools, have kept his phone ringing but unfortunately, we are all too late.

As the world of AI infiltrates all the creative jobs, writing, art, surfboards and even thought, one can’t help but lament the retirement of such a creative and free spirited approach to the life/work conundrum. If you’re looking for today’s true anti-hero in our pixelated world, I say, “All Hail Paul Blacker, and may Jah’s Light continue to burn bright in you, Brother”. Knowing what goes into a custom-made surfboard, these objects that often seem to bridge the gap between sport and spirituality, I can’t help but think that as we witness the rise of machines we will see the descent of man and some of his most important characteristics.

Thanks for reading.